Self-Forgiveness - Kol Nidre Sermon by Rabbi Tina Grimberg, September 29, 2017

07/11/2017 10:14:52 AM

| Author | |

| Date Added | |

| Automatically create summary | |

| Summary |

A white note in a shape of a dove flew past me as a late autumn wind carried it in to the sky. Shivering daveners at the Wall hurried home as the Jerusalem evening descended. The note was taken by the wind from the crevices of Western Wall and carried in to a shivering air. What happens to these notes I asked myself, never wondering before. Since I learned that one million prayer notes are placed in the crevices of the Western Wall every year. The earliest example of placing notes at the Western Wall occurred in the mid-16th century. Rabbi Gedaliah of Semitzi visited Jerusalem in 1699 and wrote the first recorded evidence of prayers being written down and left in the cracks of the Wall.

Though the Wall is considered the holiest place in Judaism; people of all faiths, including Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI, President Barak Obama, Prime Minister Steven Harper place notes in the Western Wall when they come through Jerusalem’s Old City.

I would venture to imagine that most of us have placed a note in the Western Wall at some point in our lives, human concerns are universal, most likely we ask for health, strength, peacea, express gratitude, and state our deep regrets in search of peace. Twice per year, before Rosh Hashanah and again before Passover, the notes on the Wall must be cleared out and room must be made for the large groups of new individuals coming to leave their hopes and dreams in the cracks. The Western Wall’s chief Rabbi Shmuel Rabinowitz and a team of individuals first take a ritual bath or mikveh to cleanse themselves, and then works to carefully take the notes out of the Wall with brooms and wooden sticks so as not to harm them. The notes are then placed in bags without being read by the people clearing them out, and buried in the cemetery on the Mount of Olives to the East of Jerusalem’s Old City. These slips of paper are treated the same as pieces of Torah scrolls or damaged prayer books and are forbidden to destroy.

The content of this particular note was not read by anyone, friend or a stranger, but it was told to me by its author, the middle age woman sitting on the 17th floor of Princess Margaret Hospital. We were seated on the bench in front of the elevators. Doors of which like gates of prayer closed and opened without an end.

In the words of Zelda, beloved Hebrew Poetess she writes:

“In that strange night someone asked: Can you change the past?

And the woman who was ill angrily responded:

The past is not a piece of jewelry sealed in a crystal box

Nor is it a snake preserved in a bottle of formaldehyde----

The past trembles within the present,

And when the present falls in to a pit

The past goes with it—

When the past looks towards heaven

All of life is upraised, even the distant past...”

On that floor in PMH The book of life is open, but it has few entries in it and therefore conversations with those visiting and staying tinged with stark honesty and unprecedented intimacy.

My new friend Jane was not a patient or a family member or a friend to the patient. Jane was a volunteer. Who took upon herself visiting hundreds of patients each year in order to bring them a glass of water, help them eat, or read them a book. No matter how devoted and present families were in the face of the illness, there were times patience were left alone and it was Jane who wished to fill the echoing space.

Curious of what made Jane take upon herself such hard and meaningful task I asked her about her life.

She began to tell me that a decade or so ago, her father was very ill in a hospital and Jane looked after him. On her shoulders, she cared for his needs, his finances and was the primary decision maker. Jane and her father were very close. One day after visiting her father in the morning Jane decided to order several tests in the hope of easing her father’s condition. Jane, a mother of three left the hospital to go home and feed her children. Her father seemed to rest but barely comfortably after a grueling day. Nobody thought it would be his last day. Even though every attempt was made to make him comfortable it was not a day of comfort. When she reached home she received a message from the hospital that her father had died. No amount of reasoning or convincing could have eased Jane’s regret of leaving her father on that day and agreeing to the grueling tests on his last day of life. The self-blame, guilt and regret became her constant partners. At one point visiting Jerusalem, Jane left a note in the crevice of Jerusalem stone: the note read: ”Dear God, please help me to forgive myself. I left my father on that nights without knowing that his death was near. Had I known it, I would have never left him. Please take care of his soul and help me to forgive myself for leaving him that night….”

It took about a year for the dark cloud to lift and this is when Jane decided to become a volunteer to visit hundreds of hospital beds; to hold patients’ hands; to bring water to their bedside; to hear their story.

In an attempt to soften the difficult moments of a patient’s life she was repairing what was broken in her own life. Her commitment to the cause to all those who would become ill in a strange way repaired her own past fracture. The future of her goodness repaired her pain from the past.

A study published from the Journal of Religion and Health exploring the subject of self-forgiveness observes 7 cases of individuals struggling with self-forgiveness.

Those ranging from intense rage, to traumatic childhood experiences, to relationships with parents.

…At this point, one experiences a sense of “brokenness,” an estrangement from self and others that is deeply painful. This disconnection is often accompanied by intense feelings of self-recrimination as one replays the situation in one’s mind, wracked with confusion, guilt, anxiety and despair. One’s faults and fallibilities can no longer be denied or contained. One feels agonizingly vulnerable, naked before self and others…

…There is a struggle in the midst of a deep sense of remorse. Emptiness, sadness and intense loneliness may emerge, alternating with cynicism and anger. Self-recrimination often takes the form of “beating oneself up.” At this point one is not sure whether things will ever change and one fears becoming stuck: never recovering from devastation, never moving into healing, but remaining bitter and cynical…

From the Journal of Religion and Health - Exploring Self-Forgiveness

Authors: Lin Bauer, Jack Duffy, Elizabeth Fountain, Steen Halling, Maria Holzer, Elaine Jones, Michael Leifer and Jan O. Rowe.

Maya Angelou put it well…

“I did then what I knew best, when I knew better, I did better”

If self-forgiveness or a wild life of regret…is a profoundly universal experience. The closest proof text in this conversation came to me from Masechet Brachot (7a) about Rabbi Ishmael who was the High Priest. It was an ancient priestly duty to enter the Holy of Holies on the day of Yom Kippur.

The story is told…

Rabbi Ishmael Kohen Hagadol, on Yom Kippur walked into Holy of Holies and saw the Holy One sitting of the chair of glory. And God asked him, “ Ishmael my son bless me”. And Ishmael replied: “may your attributes of mercy overcome your attributes of anger”

And he lowered his head…

A famous story well known to you is God’s profound displeasure with the Jewish People creating the golden calf (an idol) forgetting all the that monotheism was meant to offer and break from their Egyptian past.

God says to Moses: “I see that this is a stiff-necked people now let me be that my anger may blaze forth against them and that I may destroy them and make of you a great nation”. This is not the first time the deity is displeased with human behavior and regrets its creation. Noah’s flood destroys creation because of the sinful behavior of human beings. The story of Tower of Babel ends with destruction of the Tower and confusion of the languages. And yet God wants to make a new nation out of Moses.

Why would God bother after such terrible disappointments??

Because God loves a good story. At least according to Hasidic masters who said that the reason human beings were created is that God loves stories.

May I propose that I think human beings are full of wonderful surprises. What makes a good story is a good plot. What drives the plot is evolution of the characters and as the character of our own narrative we have the ability for transformation of ourselves and transformation of our reality.

We become self-architects of our spirit…

Observations over the years from my work is that you cannot talk anyone out of self-loathing or the burden of the huge responsibility that is felt for things they felt they should have done better.

No words or expressions like “don’t be so hard on yourself”; “we all do it”; “have you ever been in that situation before” – lift the burden of guilt we feel.

No logic or trained thought can be reached into that deep vulnerable childlike place where this regret finds hope.

There are no road maps or manuals that bring one out of that lonely emotional cathedral. It’s usually a place for one but the world including this sanctuary tonight is filled with these one-off structures. They are all a particular architecture and are uniquely constructed with our personal stories.

On this Yom Kippur among the list of all we have done wrong can we also include the list of all we have done right.

Jane’s self-guilt and lack of self-forgiveness kept her in a tiny cathedral of darkness. She missed the camera view and the context of which her departure from the hospital occurred. She was sleep deprived; she had three children who waited for her at home; she attended to hundreds of details throughout her father illness with such care -- she hung melodies near his bedside. She was an outstanding daughter. Self-forgiveness involves seeing oneself in a broader context of things. It’s true that some things we could have done better but we forget the hundreds of things we’ve done extremely well.

On this Yom Kippur we are meant to ask and grant forgiveness. If you can be kind and merciful to your own self, we have a greater chance to be kind and merciful to others. For most of the wrongs done to us we have done ourselves.

There is no death without regret

The past trembles within the present,

And when the present falls into a pit

The past goes with it—

When the past looks towards heaven

All of life is upraised, even the distant past...”

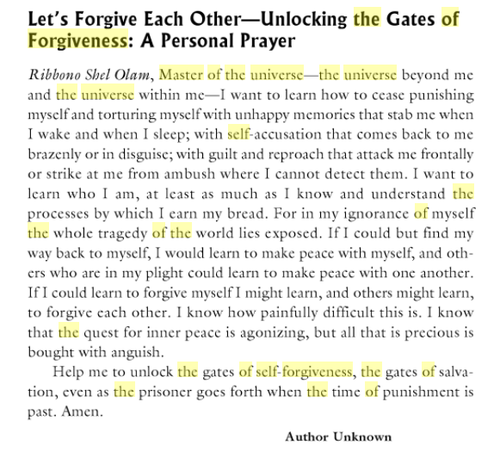

I would like to conclude with a prayer whose author we do not know but speaks poignantly to our struggle…

It is called:

A wonderful ma’aseh also shows Reb Elimelekh’s continued preoccupation with divine justice.

Once, a Hasid arrived in Lizhensk before Yom Kippur to learn from Reb Elimelekh how he did his own kapporot (atonement), but Reb Elimelekh said, “I can’t let you be present for that, but please pay a visit to the local innkeeper and watch him carefully.” So the Hasid obtained a room at the inn and took a seat in the common room where he could observe the innkeeper without being noticed. Late that night, when the rest of the guests had gone to bed, he remained in a dark corner of the room observing the innkeeper, who sat down at a table with a candle and took out two journals. He began to read from the first in a low voice. The Hasid could hear only just enough to know it was a list of wrongs he had committed during the year. Then he closed the book and opened the second book and began to read; that it seemed was a book of wrongs he had suffered during the year!

Then he closed this book as well and set the two side by side and said, “Ribbono shel Olam, if You’ll forgive me for the wrong that I’ve done to You, then I’ll forgive You for what You’ve done to me”

Thu, 18 April 2024

10 Nisan 5784

Upcoming Programs & Events

Apr 18 Ma Nishma? What's Happening in Israel? Thursday, Apr 18 7:00pm |

Apr 23 Passover Services Tuesday, Apr 23 9:00am |

Apr 23 Second Night Passover Seder Tuesday, Apr 23 6:30pm |

Apr 27 Join us to say Todah Raba and L’Hitraot to Yaron! Shabbat, Apr 27 10:00am |

Apr 29 Passover Services Monday, Apr 29 9:00am |

This week's Torah portion is Parashat M'tzora

| Shabbat, Apr 20 |

Candle Lighting

| Friday, Apr 19, 7:53pm |

Havdalah

| Motzei Shabbat, Apr 20, 8:58pm |

Erev Passover

| Monday, Apr 22 |

Subscribe to our Friends of Darchei Noam Mailing List